Global CEOs Weigh the Risk of Doing Business in China as Tensions Rise

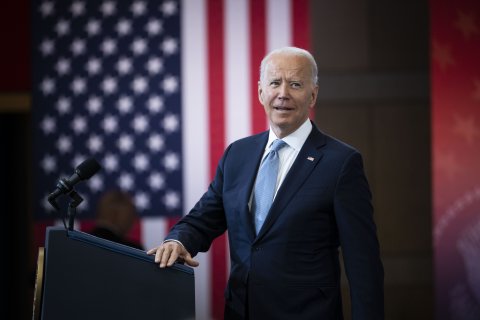

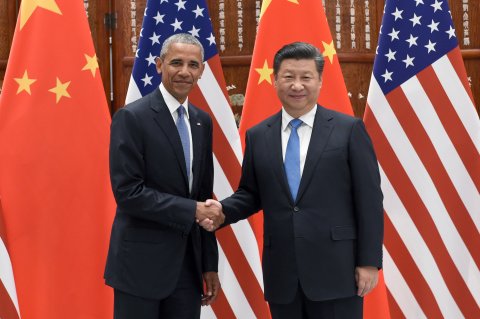

9 min readFor multinational companies, the ever-increasing tension between Beijing and its trading partners complicates the challenge of doing business in China. Just last month, the National Security Agency got wind of a massive cyber hack underway into Microsoft’s Exchange email server. Within hours the NSA had determined where the assault had originated: the People’s Republic of China. The PRC had over the years repeatedly forsworn any intention to hack into U.S. corporate computer systems and steal intellectual property. President Xi Jinping, in fact, had given Barack Obama his word, in September 2015, that China would not engage in commercial cyber espionage.

That was a lie, and now the Biden White House was fed up. While refraining, for the moment, to impose new sanctions against Beijing, it immediately contacted key allies, led by Japan, and asked them to join Washington in issuing a formal joint complaint to Beijing, which they did in late July.

This marked a difference from the aggressively unilateral approach on trade that the Trump administration took, and was the first significant demonstration that the Biden administration meant it when it said it would work closely with allies to respond to China’s economic predations.

Drew Angerer/Getty

In government offices in Tokyo and in European capitals, the change was welcome. “Now, on cyber security, we will be working closely with the United States, as well as other like-minded countries, to take countermeasures,” Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga told Newsweek in an exclusive interview, via Zoom, during the Tokyo Olympics. “This is going to be a public-private effort. And in that, we’ll be working closely with the United States.”

Given how intertwined Tokyo’s economy is with China’s, Japanese companies are very much in the crosshairs. Japan over the past 30 years has poured $140 billion in direct investment into China, compared to $110 billion from the U.S. Tokyo now trades more with China than with the United States, as does Washington’s other key East Asian ally, South Korea.

Ever since Deng Xiaoping reopened China to the world in 1979, the country has seemed a promised land for businessmen and women around the world. First as a source of virtually limitless low wage labor with which to make their products, then as a vast market itself, the allure of the China Dream was unmatched.

To some extent, as the trade and investment statistics illustrate, that dream has been realized. But now, with escalating friction over trade and human rights, doing business with China is fraught. As the West squares off with Beijing in the 21st century’s version of the Cold War, multinational companies are caught in the middle. As Matt Pottinger, President Trump’s Deputy National Security Adviser says, “the ideological dimension of the competition [between China and the West] is inescapable, even central.” CEOs—in the U.S., Japan and across the developed world—”need to come to grips with how much the situation has changed over the past few years and acknowledge that those changes are almost certainly here to stay.”

This is the last place most CEOs ever thought they would be. Many companies have invested decades of time and millions of dollars setting up business in China. Auto companies like Volkswagen, Toyota and General Motors have joint ventures producing cars all over the country. In 2013, China became GM’s largest market, and it has remained so ever since. Intel spent $2.5 billion on a new computer chip factory in Dalian in northeast China.

KIMIMASA MAYAMA/POOL/AFP/Getty

More and more, those companies’ home governments are wondering whether those investments were wise. And Beijing is pressuring them to behave. When Biden assumed office, China waged a furious lobbying campaign aimed at CEOs in the U.S. and allied countries like Japan. Beijing urged them to weigh in against Trump-era trade restrictions. In a virtual meeting in February, Beijing’s top diplomat, Yang Jiechi, told a group of American businessmen and former government officials that China was still very much open for business, but warned that issues like Tibet, Hong Kong, Xinjiang (where thousands of ethnic Uighurs are imprisoned) and Taiwan were “red lines” they must avoid.

As Pottinger said in a speech at Stanford’s Hoover Institution in late March, “Beijing’s message was unmistakable: You must choose. If you want to do business in China, it must be at the expense of American values.”

U.S. allies heard the message as well. Many multinationals have already seen their businesses suffer as trade conflict ratcheted up. European powerhouse Ericsson AB, the second largest maker of cellular equipment in the world, said in mid-July that its sales in China had plunged, and warned that its market share there would likely diminish sharply in the coming months. The reason? Sweden late last year banned China’s Huawei from the country’s buildout of its 5G telecommunications network.

Multinational companies in every industry doing business in China are acutely aware that as the geopolitical environment worsens, all the money and effort they have put into building their businesses there could be at risk. In a recent, candid interview with Newsweek, Takeshi Niinami, the chief executive officer of Suntory, the Tokyo-based beer and spirits maker, said when weighing the risks of expanding the company’s business in China, he and his team of senior executives must confront the possibility of a worst-case scenario: confiscation.

Shiho Fukada/Bloomberg/Getty

“We have to decide whether to expand production facilities or not in China,” Niinami says. “Should we invest more knowing that the possibility of confiscation [exists]? Do we take the risk or not—and to what extent? If it’s a 10 billion [yen investment], maybe not. Five billion? Probably. So we have to judge to what extent we can tolerate confiscation.”

Global CEOs are rarely so blunt when discussing their business in China, but Suntory’s risk analysis is rooted in reality. Beijing already has a record of punishing companies from countries who make decisions it disapproves of. In early 2017, giant South Korea retailer Lotte agreed to give land it owned to the Seoul government so that the U.S. could build a missile defense system aimed at deterring North Korea. Beijing insisted that the system’s radar could also track its own military flights, and launched an economic war against the giant South Korean retailer. For months it shuttered Lotte’s 10 stores across the country and disrupted its duty free shopping website—costing the company nearly $200 million in sales.

Zhang Peng/LightRocket/Getty

For countries like Japan and other developed economies, there are two primary concerns facing them and their companies. One is the increasing techno-national competition between Beijing and the West. In 2015, China issued an ambitious plan to develop leading companies in a wide array of high tech industries—from biotechnology to robotics to telecommunications and beyond. Among its goals is to have 70 percent of the components used in its own high tech industries be sourced domestically. And by 2049—the 100th anniversary of the Communist Party coming to power in Beijing—it seeks to have world class competitors in no less than 14 key high tech industries.

For an industrially sophisticated, high-tech nation like Japan, China 2025 presents a big problem. CEOs like Niinami of Suntory can continue to invest in China in pursuit of 1.3 billion customers, knowing that its business isn’t targeted by Chinese economic planners. “But not technology companies,” Niinami told Newsweek. Companies like Fanuc in industrial robotics, or Toshiba and Fujitsu in artificial intelligence, can no longer look at China as an ordinary market. High tech companies “have to view Beijing as a predator, and protect their intellectual property at all costs,” says a former board member at Nissan, the Tokyo-based automaker, who requested anonymity in order to speak candidly.

The other driver of corporate investment decisions is the fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic, which originated in China and showed multinational companies across the world just how vulnerable their supply chains are. In mid-June the Biden administration completed its 100-day review of U.S. supply-chain vulnerabilities. The results were eye-opening and, for a lot of companies, depressing. The review called for sweeping changes in how the government interacts with private companies, offers subsidies to a range of high tech industries (just as Beijing does) and presses companies to bring back supply chains long ago offshored to China.

Sebastian Kahnert/picture alliance/Getty

Prime Minister Suga was ahead of the U.S. president. Last year, Tokyo announced that it would devote $650 million in subsidies to help 87 companies move manufacturing out of China to either southeast Asia or back to Japan. Some analysts heralded the announcement as the commencement of a great “decoupling” of the Japanese economy from China’s.

It wasn’t. As Scott Kennedy, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington, D.C., think tank, points out, “a perusal of the list of companies receiving aid are small and medium-sized enterprises, not major Japanese manufacturers with extensive investments in China.” Moreover, a substantial portion of them are in two sectors—medical equipment and specialty chemicals—which were in high demand during the pandemic. Altogether, the Suga subsidy program affects just 1 percent of total Japanese investment in China.

Balancing an economic relationship with China against a worsening geopolitical climate is a delicate, complicated business. For major companies across the globe, the China dream—a huge, prosperous country with a massive middle class snapping up their wares—dies hard.

Consider the case of Microsoft. If the Biden administration was angry over China’s cyberattack against the tech behemoth, Microsoft’s management was embarrassed. The company over the years has endured Chinese abuse and constantly come back for more. For years, you could buy pirated versions of Microsoft’s Windows computer operating system and programs like Word from street vendors in Beijing and Shanghai for the equivalent of a couple of bucks. Microsoft kept accepting Beijing’s assurances that things would get better, and right up to this day has kept investing. Less than one month before the July cyberattack against its Exchange system, Bloomberg and other news agencies reported that Microsoft intended to invest billions of dollars in four new massive data centers in China, in the hopes of capturing Chinese businesses moving to store their data in the cloud.

What happens now?

For multinational companies and governments alike, the Microsoft news this summer neatly captured the dilemma of dealing with Beijing. Reconciling the economic opportunity China still presents with the present dangers it poses will be a critical task for years to come. As Suntory’s CEO Niinami suggests, companies producing run-of-the-mill consumer goods can relax because nothing much about their China business will change (aside from the fact that their competitors continually become more formidable).

Wang Zhou/Pool/Getty

But technology companies, particularly those that Beijing singles out in its Made in China 2025 program, are in for a rough ride. For them, Deng Xiaoping’s famous mantra of “reform and opening” has been replaced by “reform and closing,” says James McGregor, the former head of the American Chamber of Commerce in Beijing, now Greater China Chairman for consulting firm APCO Worldwide. The computer chip industry, McGregor says, is “at the top of the list of America’s threatened industries.” American chip makers are going to have to re-evaluate their China presence, and confront the likelihood that the huge and lucrative market will be controlled by domestic competitors in the coming decades.

That is likely to be true in a number of other businesses, from machine tools and robotics to new energy materials. Beijing seeks to dominate these industries. The task for multinationals and their home governments going forward will be to play defense to the greatest extent possible: push back against intellectual property theft as vigorously as possible to force Beijing to achieve its ambitious economic goals on its own.

For CEOS across the globe, that is hardly the stuff of which China Dreams are made. But it is the bleak reality confronting them now.