Forty years ago this week, MTV changed everything in the music business | Arts & Culture | Spokane | The Pacific Northwest Inlander

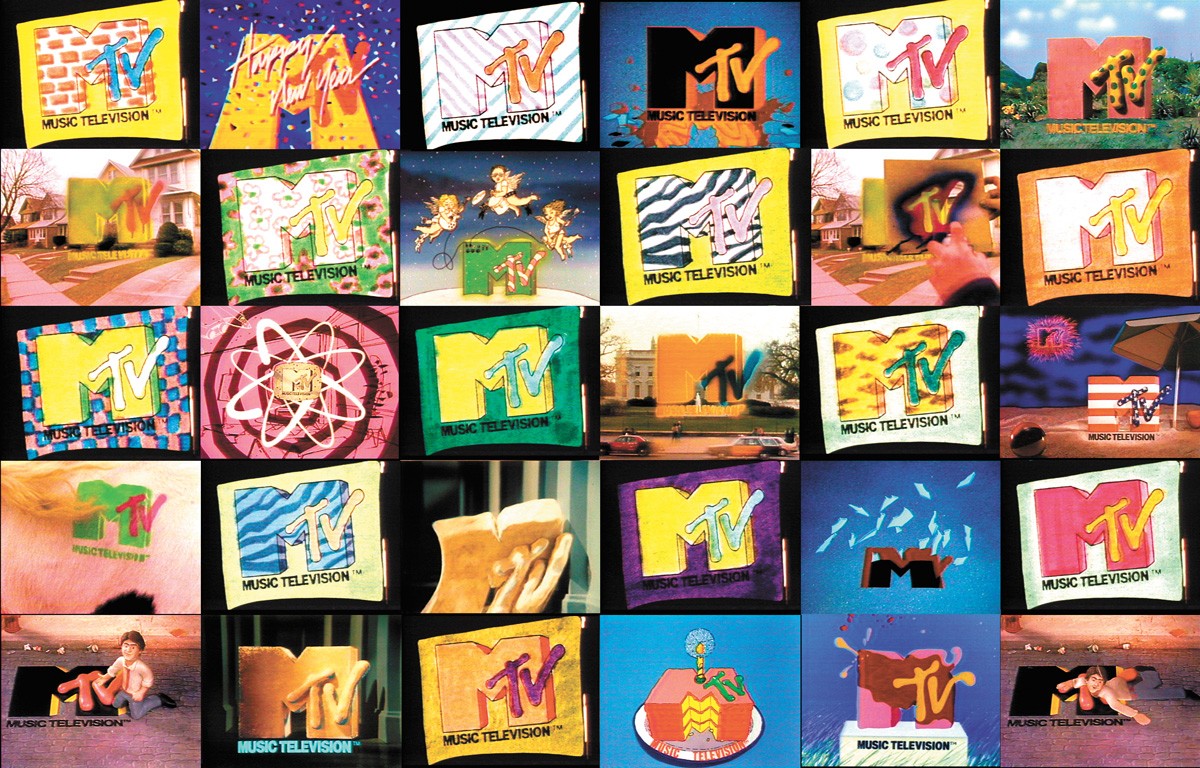

12 min readIt’s obvious now, but when MTV first launched 40 years ago this summer, the idea was relatively novel that a musical artist would feel compelled to make mini-movie versions of their songs.

That’s abundantly clear when you go back and watch the first couple of hours of videos that aired on Aug. 1, 1981, on the channel that soon revolutionized the music industry, for good or ill depending on your point of view (and probably your age). Clearly, based on those early videos, they launched a channel before most record labels or bands thought much about making a killer visual product.

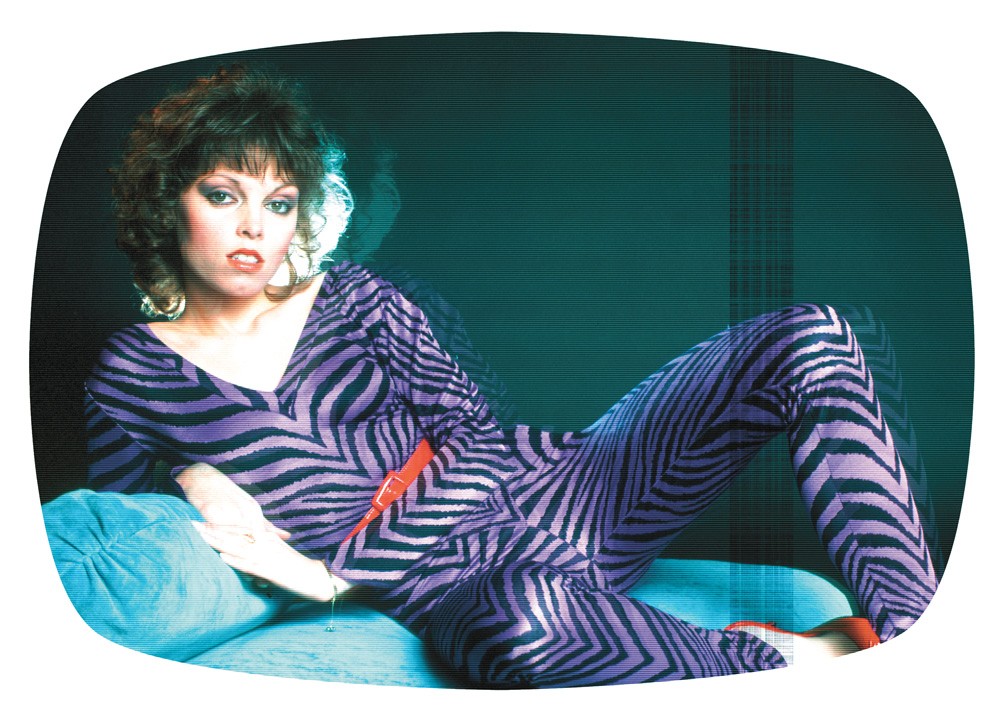

The production values on most of the early options? Pretty terrible. The playlist that first day? Male-dominated save for Pat Benatar and the Pretenders, and almost oddly diverse because they had to play whatever videos they had access to, and there weren’t many yet. The hosts? They were “VJs” because they were “video jockeys” compared to their radio counterpart disc jockeys, a generally amiable blend of fresh talent (Martha Quinn was 22 and just out of college) and radio veterans like JJ Jackson and Mark Goodman.

The channel had issues with inclusivity early on and became pretty formulaic in time before eventually abandoning music almost completely in favor of lifestyle shows, teen-oriented programming and reality dreck. But there’s also no denying the massive influence MTV had on kids’ music tastes. Suddenly teens in middle America were being exposed to the likes of androgynous Brits like Culture Club, cool club kids like Madonna and, eventually, boundary-pushing artists like Prince. While Top 40 radio was full of Styx and REO Speedwagon when MTV appeared, it soon shifted toward what MTV was delivering, and that’s not a bad thing. Because while it took MTV a couple years to start playing Black artists, Top 40 went from lots of shlock rock balladry to include synth-pop, soul and R&B, hard rock, and New Wave, all blended together by artists from around the world.

“One of the things about MTV that people don’t realize is that when it launched, it launched in very small markets. They were testing it out,” says Stephen Pitalo, a New York-based music and entertainment journalist and publisher of the new digital magazine Music Video Time Machine. “Aug. 1, 1981, is a big deal because that’s when MTV launched, but LA and New York didn’t get MTV until 1983. They were hitting these small markets, and the reason it grew so quickly is because these small markets like Tulsa, there was a huge spike in records they were selling that coincided with the music videos playing on MTV. When the record store in Tulsa is selling Duran Duran, there has to be some reason that it’s happening.

“One of the things I love about this era is that it turned the pop charts into the most schizophrenic free-for-alls in the history of music. If you look at what was on the charts in 1983, there’s so much going on. And the only thing they have in common is MTV — that their videos were playing.”

Ann Ciasullo, a Gonzaga University English professor whose research often delves into ’80s pop culture, remembers Spokane being one of those small towns where MTV had a huge impact on her and her friends. She was 11 when the channel debuted, giving her and her four-years-older sister, Lori, ample opportunity to watch their favorites like Pat Benatar.

“My sister and I nagged our parents to get cable so we could get MTV,” Ciasullo says. “I know we had it in 1982 because I remember watching Journey’s concert, and this was a big neighborhood deal because my friends and I were all fans.

“One of the great things about MTV is, we were a small town at that point, and you’re seeing Adam and the Ants and David Bowie and a lot of weird stuff that you’re not going to see walking around the streets of downtown Spokane.”

Bob Gallagher opened his record store 4,000 Holes in Spokane in 1989, and he doesn’t recall any particular sales bumps driven by MTV as he was dealing more in rare collectibles than new artists at the time. But he concurs that the arrival of the channel opened his eyes to a lot of new music he might never have heard otherwise.

“There’s no denying what MTV did for rock ‘n’ roll,” Gallagher says. “It just opened the doors for so many bands that I never would have experienced. Even something as simple as Def Leppard. I might hear something on the radio but never pay much attention, until the ‘Photograph’ video, then my ears perked up a bit.”

GLORY DAYS

None of the music business people expected MTV to work. As author Rob Tennanbaum notes in the 2011 book he co-authored with Craig Marks, I Want My MTV: The Uncensored Story of the Music Video Revolution, the overwhelming response to creating a channel dedicated to music videos was that it “seemed like an asinine idea.”

That asinine idea would soon become a global phenomenon, including being the subject of a $525 million bidding war five years after its debut. That was real money in the mid-1980s! By 1987, MTV Europe launched the first of many global versions of the channel, but before all the worldwide pop cultural domination could get started, MTV had to survive its first unsure steps.

When the channel aired Buggles’ “Video Killed The Radio Star” as its first video, the idea was basically to be FM radio, but on TV. The problem, though, is that the artists glutting America’s radio airwaves rarely had bothered to make a music video. That’s why the first months of MTV were so full of folks like Rod Stewart, Pat Benatar, Queen and live concert clips culled from ’70s-era bands.

MTV only had about 100 videos to rotate through when it launched, Tannenbaum writes, and the business plan was predicated on convincing record companies to make more videos, and to pay for making those videos, and then ultimately give those videos to MTV for free to put on the air. That seems crazy in retrospect, but damn if it didn’t work, especially after the record label suits saw those record sales increase in places like Spokane for bands getting a lot of play on MTV.

“A feature of early MTV was at the top of every hour, they’d show the logo and [play] the theme,” Ciasullo says. “And they’d tell you what was coming up. So you’d tune in to see, is this an hour I want to spend hanging out to see if they’re going to show a video I want? There was a lot of anticipation involved in it.

“We kind of grew up on TV, we had our own little TV room, and MTV was on all the time. All the time. I feel like we were just constantly waiting to see either a new video, or ‘When will we see Pat Benatar?’ or “When will we see Journey?’ I have a Polaroid picture of the TV with [Journey frontman] Steve Perry on it — that’s how much we were watching it.”

Pitalo was growing up in Biloxi, Mississippi, when MTV hit, but his experience was much the same as Ciasullo.

“We’re talking about junior high, high school and college, that was 1980 to 1990 for me, so I am the MTV generation,” Pitalo says. “It was not readily available in my region at first. And also it was an added channel, it wasn’t basic cable. You had to order it along with other channels that came along with it.”

Pitalo, who’s interviewed hundreds of artists and video directors from MTV’s heyday, notes that the form was a natural for some artists who used MTV to propel themselves into stardom, folks like Madonna and Culture Club and Billy Idol. “And it was also a weird testing ground right at that moment for who was going to graduate from the ’70s and become part of this big deal.”

“There was just no way to know who was going to work and who was not,” Pitalo says. “Who would have guessed that singer/songwriters like Bruce Springsteen and Billy Joel would thrive in this new era, then there were contemporaries of theirs that it just wouldn’t work out for.”

4,000 Holes’ Gallagher recalls the cheesy special effects of early Tom Petty videos, even as the classic rocker later made more memorable clips. And though he wasn’t enamored with all the shiny new acts on the channel, he wasn’t immune to MTV’s charms.

“It was probably the beginning of an almost video game-like era, when we started sitting in front of this screen mindlessly for hours,” he says. “That was really the first time I remember sitting down and watching, well, nothing really. Just one video after another.”

NOT SO QUIET ON THE SET

MTV worked out just fine for artists across virtually every genre you can think of for most of the ’80s. As Tannenbaum writes in I Want My MTV, the channel “could make stars out of Brits in eyeliner, rappers in genie pants, permed Jersey boys, even choreographers with weak singing voices.” Readers of the MTV Generation probably know exactly who he’s talking about in each of those categories.

Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” video for the title track of his second solo album was a cultural phenomenon and helped open doors for other Black artists who’d been largely ignored in the early days of the channel. Prince, Madonna and Bruce Springsteen, as well as the slew of artists known as the “Second British Invasion” (including Duran Duran, Eurythmics, Spandau Ballet, etc.), all saw their popularity soar as MTV expanded across the United States. Within a couple years of MTV’s launch, musicians were pretty much expected to make videos to accompany their new songs. Some embraced this new aspect of the music business, while others (notably Metallica for several early albums) used their refusal to make a video as a badge of “cool.”

Richard Marx’s self-titled debut arrived in 1987, and the pop-rocker tells the Inlander the effect of MTV on his career was “massive, really life-changing.” He recalls that his first single, “Don’t Mean Nothing,” was being pushed by his record label primarily to rock radio. It was a rock song, after all, and three Eagles performed on the track, so rock radio was a natural place. Pop radio, not so much.

Then, Marx says, MTV decided to air the video and declared it a “hip clip of the week,” which meant “Don’t Mean Nothing” would be played seven times a day, for seven straight days.

“I remember being at 7-Eleven on Monday, and nobody even looking twice at me,” Marx says. “And then the next day going somewhere and having a crowd of people following me and coming up to me and asking for my autograph. Like, literally overnight, ‘Holy shit, I can’t believe this is happening!'” And it blew up from there. “MTV was incredibly helpful. I was giving them what they liked to play, and they were helping me sell records. It was a huge, huge component to my success.”

Of course, just because they helped Marx doesn’t mean he enjoyed the process. He understood making videos was part of his job, a “really important component to keeping this train moving,” but the actual process of making them?

“I absolutely hated it,” Marx says. “The actual conceptualizing, and particularly being in them, was never something I enjoyed. I hated it. It was a lot of standing around waiting, and sitting in a trailer waiting for them to light something. I didn’t have the patience for it. Every time it was time for a new video, I’d go, ‘Motherf—-er, I f—-ing hate this!'”

For hip-hop group Cypress Hill, MTV’s embrace of rap music and hip-hop culture toward the end of the ’80s was instrumental in connecting the band to an audience outside their Los Angeles home base. The pioneering Yo! MTV Raps showcase for hip-hop videos started on MTV in 1988 just as Cypress Hill landed a record deal. Their first single and video didn’t make much noise, but when their breakthrough “How I Could Just Kill A Man” started getting airplay, their label rushed them off tour to New York City to film a video as quickly as possible.

The video helped Cypress Hill explode and start one of the more successful and long-running careers in the genre, but co-founder Sen Dog told the Inlander the “Kill A Man” video started a lot of confusion about the group because of its New York setting. For years they had to explain to people they were actually an LA crew. Even so, he credits MTV and videos for helping launch the group, and says he always enjoyed the process more than Marx did. Given Cypress Hill’s predilection for massive amounts of weed, that’s not a shock.

“Videos were always fun; you get a chance to hang out with your boys all day long,” Sen Dog says. “Film, smoke some herb, drink some beer, eat some good food and, you know, film a video. You get to jam your song all day long. It was fun for me; it wasn’t a thing like I felt like I was working.

“When our first video, ‘The Phunky Feel One,’ came out and they put it on Yo! MTV Raps, man, you could have knocked me over with a feather. I just kept looking at myself the whole way through. The first time I saw it, I kept looking at me. Later on you watch the whole video because you get over the fact your whole entity is on MTV Raps, and you look at when they played you in the show, who they played before and after, and all that.”

REALITY KILLED THE VIDEO STAR

MTV still exists, but if you go turn it on right now, it’s likely just another episode of Rob Dyrdek’s Ridiculousness or Catfish: The TV Show. It’s been decades since music videos were the main ingredient on MTV, despite those initials allegedly meaning “music television.”

Author Tannenbaum considers 1981 to 1992 to be MTV’s “golden era,” and that end date coincides with the debut of MTV’s The Real World, the first of many reality shows to take over the channel, and the first major move away from playing music videos.

Gonzaga professor Ciasullo recalls MTV losing its way even earlier. First the emphasis moved from the creative videos delivered by stylish, androgynous British bands to more stage performances by hard rock acts, accompanied by a side of serious misogyny.

“There’s a major shift in MTV’s programming in the mid- to late ’80s toward more metal, and those videos are just, frankly, a lot less interesting,” Ciasullo says. “I remember kind of wrapping up with MTV around my first year of college. At that point, they just weren’t showing videos as often.”

Pitalo reveres MTV’s golden age for its creativity in both the music and filmmaking, noting that several Hollywood heavyweights like David Fincher (working with Rick Springfield) and Michael Bay (working with Divinyls) got their starts in music videos.

“The music video directors I’ve talked to, one of the things they said over and over was that the early period was just such a sweet spot,” Pitalo says. “The common opinion was, ‘We never had enough money and we never had enough time, but I never had more fun and I never enjoyed my career more than when I was doing that.'”

As MTV devolved into lifestyle programming and music videos were left aside in the 40 years since the channel debuted, Pitalo thinks we’ve lost more than just an entertaining outlet.

“We live in a very unfortunately on-demand society when it comes to media,” Pitalo says. “And if it’s very easy to get, there’s that part of us that thinks that it has less value.

“You used to have to watch MTV, and wait. You had to wait for the thing you wanted to see. And you might not get to see it! And you have the choice of everything now. And you know what? The choice of everything now has not made it better. It has not made any form of media better.”

MTV lost its way when it decided to focus more on the television than the music, Pitalo says, and while he’s depressed by how “there’s no variety on the pop charts anymore,” he does get some retrofied joy when he VJs dance parties in New York, spinning videos from MTV’s better days.

“Basically, I’m a DJ but I’m playing videos on giant screens, and I stick to the ’80s and ’90s,” Pitalo says. “People come out, they want to dance. And the young, young kids who love the ’80s and ’90s don’t love it because it’s nostalgia. They love it because of what it is. Then there’s people who will come out who are my age or a little younger, that are like, ‘I love this, I haven’t seen these for so long.’

“When I’m doing a gig, and I’m mixing Toni Basil’s ‘Hey Mickey’ with Outkast’s ‘Hey Ya!’ and they totally embrace it, I know there’s hope.” ♦